Defiant, the ships of the British Army poised their sails to complete their journey towards the far-flung coast. At the proper distance away from the shallow beach, the anchors slid quickly into the watery darkness and connected with the bottom of the Guinea Coast. Watching above from the slow gliding clouds, the silhouette of several dark teardrops left their larger hosts and meandered their way towards a long sandy break on the rocks. Determined, their final destination was finally within close view.

Men of war rode the sickening lift and fall of the immense silver water clutching and swaying their heavy oars from knee to chest, knee to chest, knee to chest. All eyes watched the contours of the distant horizon. Small fires fueled whiffs of smoke at various spots at the edge of the water. Shifting red coats moved about, out of place, along the grey stonewalls of the fortress. The encampments drew the eyes of the men to the dark forested background beyond the beachhead. Alien. Birds zipped and circled above the edge of the water, and the smell of the fires mingled with the hot, salty air of the Gold Coast. …

- Check out this free digitized source: http://archive.org.

- Primary source writing about the Red River Expedition:

- Wrote The Soldier’s Pocketbook, 1869

- Blackwoods December 1870

- Directorate of History and Heritage 83/309: Narrative of the Red River Expedition: By an Officer of the Expeditionary Force, 1870

- Library and Archives Canada, Manuscript Group 29-E111 Journal of the Red River Rebellion

- Captain G.L. Huyshe. The Red River Expedition (London: MacMillan and Co.) 1871.

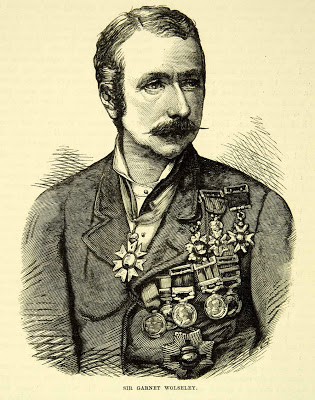

- Colonel Wolseley’s official account: Correspondence relative to the recent Expedition to the Red River Settlement: with Journal of Operations, 1871. This wonderfully detailed source is full of implicit and explicit details about the RRE. So far, it is particularly interesting how the British and Canadian intelligentsia wanted to ensure the largely Canadian militia force, although augmented by a regiment of the British 60th Rifles, would be a display of “imperial” power against Riel for the Canadian public. This small detail shows me the documentation from the period is full of promising details and perspectives for my handling of Wolseley. Now I have to keep making time to finish this part of the research so I can start writing the first chapter. Maybe I can have it finished before summer?

![ghana-ashanti-war-garnet-wolseley-troops-dunquah-1873-106886-p[ekm]400x261[ekm]](https://tonykayeblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/ghana-ashanti-war-garnet-wolseley-troops-dunquah-1873-106886-pekm400x261ekm.jpg?w=474)